After the fall of Sana’a

WHIA Editorial

by Marah Bukai

Translation from Arabic by Dean Aesh

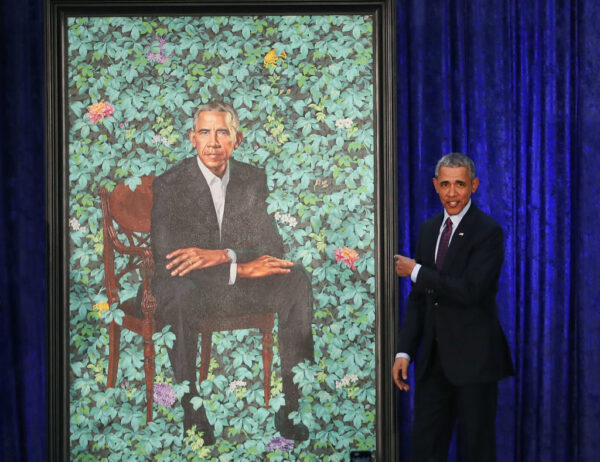

The democratic administration’s approach to the Iran nuclear issue is deeply rooted in the Democratic Party’s longstanding political vision, which was notably championed by President Barack Obama.

That vision was embedded by a firm decision during the administration of former President Jimmy Carter, who opted to support the rising revolution of Imam Khomeini in 1979. The ideological foundation of this decision, which has shaped U.S.-Iran relations for decades, was built upon the Islamic Green Belt theory. This theory, conceptualized and strategized by Zbigniew Brzezinski, Carter’s National Security Advisor and fellow Democrat, predicted that the emergence of U.S.-backed Islamic regimes across the Middle East—anchored in popular support derived from Islam—could serve as viable alternatives to the region’s entrenched authoritarian regimes while simultaneously curbing the influence of Soviet-aligned leftist movements.

To signal his endorsement of the newly established Mullah regime in Iran, Carter lifted the embargo on arms and goods sales to Iran, which had been in place since 1978. Carter’s affinity for supporting the clerical establishment was further underscored by his refusal to grant a visa to the Shah of Iran, a close U.S. ally, thereby denying him entry into the United States for medical treatment in New York before his death from a terminal illness.

However, Carter’s stance did little to prevent the growing tide of anti-American sentiment in Tehran, which culminated in the November 4, 1979, seizure of the U.S. embassy, where American diplomats were held hostage for 444 days. This event laid the groundwork for a protracted conflict with the American West, initiating a chain of violence that began with the Khomeini revolution over three decades ago, extended through the 1983 bombing of the U.S. Marine barracks in Beirut, and reached its peak with the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks on American soil.

The puzling nature of the Washington-Tehran relationship has long provoked curiosity and confusion across various spheres. However, the oscillating dynamics between these two adversaries are dictated by their shifting strategic interests, which alternate between rapprochement and estrangement in different regions of the world. Their shared priorities were exemplified during the U.S. invasion of Afghanistan in 2001, which resulted in the fall of the fundamentalist Taliban regime. Iran, in turn, experienced relief from the Salafist tension on its right corner, while the Americans dismantled Saddam Hussein’s chauvinist regime.

This recovery provided Tehran with a robust foundation to expanding its influence across multiple Arab countries, establishing a militia and military presence in Lebanon, Syria, Iraq, and Yemen. Likewise, the declaration made by Ali Reza Zakani, Tehran’s representative in the Iranian parliament and a close associate of Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei, was not without basis when he claimed that “Four Arab capitals are now in Iran’s hands and have joined the Iranian revolution after the fall of Sana’a!”