The Syrian Conflict: The Myth of Containment and the Realities of Accountability

One of the most unforgiving aspects of the Syrian Conflict is the fact that its tragic episodes have unfolded in full light of day. No self-respecting journalist or policymaker can claim ignorance of their true nature. We knew of various developments that included arrests and bombings, instances of ethnic cleansing and cold-blooded massacres almost as they happened. Everything was reported in real time and documented in sound and picture. Even the horrible industrial-scale killings that took place in security centres and prisons, turned into veritable liquidation camps, did not escape this documentary trend due to myriad leaks and the brave whistle-blowers behind them.

Despite all this, there were still those who chose not to see. Those who refused to believe what they were seeing, those whose interests made them disregard the truth and invest in misinformation, and those whose worldview and political calculations made them reluctant to act decisively to put an end to the unfolding tragedy. The result was another failure in living up to the ‘Never Again’ promises, regarding instances of genocide, and that failure has had implications for global security everywhere. It has upended political processes in countries far beyond the Middle East and has served to undermine the ‘Liberal Global Order’ on various levels. Without understanding the ‘How’ and ‘Why’ of these assertions, we risk repeating our mistakes in relation to other conflicts. No less importantly, we risk failing in Syria again, where the struggle is far from over and far from being as contained as it appears.

In this short essay, I will briefly relate my impressions on the myth of containment of certain conflicts in an age of hyper-connectivity, on how such conflicts play out on the global stage, and on domestic scenes in various countries in an age of increasing political polarisation. I will also deal with the ‘usefulness’ of these conflicts to certain actors on the one hand, and the danger they pose to the interest of others on the other hand. Finally, I will deal with the global implications of neglecting the issue of accountability in regard to war criminals now turned drug kingpins as well.

Let’s start with the basics

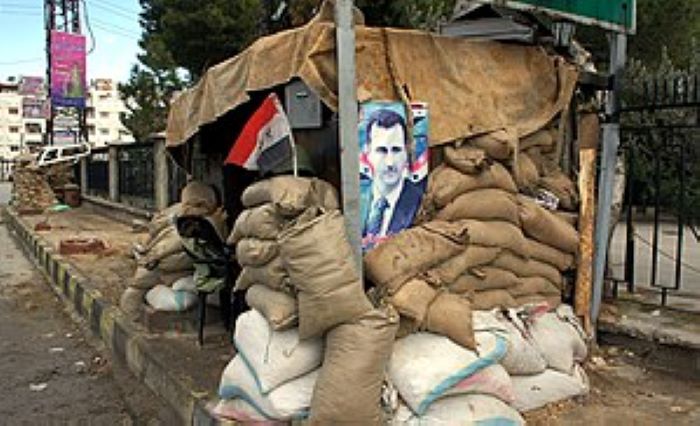

The conflict in Syria did not start out as an armed insurgency, but as a largely peaceful protest movement against official corruption and authoritarian methods. It only turned into a violent insurrection following months of violent crackdown by the ruling regime of Bashar al-Assad. This is how the BBC describes this development.

In March 2011, pro.-democracy demonstrations erupted in the southern city of Deraa, inspired by uprisings in neighbouring countries against repressive rulers. When the Syrian government used deadly force to crush the dissent, protests demanding the president’s resignation erupted nationwide. The unrest spread and the crackdown intensified. Opposition supporters took up arms, first to defend themselves and later to rid their areas of security forces. Mr Assad vowed to crush what he called ‘foreign-backed terrorism.[1]

The decision to take up arms was slow in the making on part of the protesters. Their preference in the face of the Assad regime’s violence and its deployment of tanks and artillery against unarmed civilians was to call on the international community to impose a no-fly zone over the country and to target the regime’s military infrastructure thus crippling its capacity to wage war against them. Such a step, they hoped, would force the regime into negotiating with opposition groups paving the way for political transition. As usual, in these critical moments, the international community waited for the occupants of the White House to lead the way, but the Obama Administration at the time had other concerns and priorities.

Despite his promise to the American people to end America’s involvement in conflicts abroad, especially in Iraq and Afghanistan, President Barack Obama had already found himself authorising the US military to lead NATO’s operations against the Libyan dictator Muammar Qaddafi. The intensive operations lasted throughout most of 2011, that is, at the same time Syrians were demanding international intervention. As such, despite President Obama’s call on Assad to ‘get out of the way’, the prospect of any direct US military move at that stage was categorically shut down.[2]

As violence escalated, protesters, now joined by thousands of defectors from Assad’s armies, were forced to take up arms. Meanwhile, regional powers, led by Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and Turkey, began pouring money to support various rebel militias while pressing their American ally to get more involved. In mid-2012, President Obama sent military advisors and equipment to Turkey and Jordan to increase the fighting efficiency of moderate rebels operating in the southern parts of the country in the hope of forcing Assad to the negotiation table.[3] For all the conspiracy theories that proliferated before and since, that was the extent of America’s military involvement in supporting Syria’s rebels. The end goal for the Obama Administration has always been a negotiated transition rather than the kind of regime change that took place in Libya, not to mention Iraq. ‘There is no military solution’ to the Syrian Conflict became the often-repeated mantra in official briefings at the time.[4] These tactics only served to push Assad into further reliance on Iran, Lebanon’s Hezbollah, and various Shiite militias funded and trained by Iran and made up mostly of Iraqi mercenaries and Afghan refugees.

In September 2012, President Obama drew his (in)famous red line on the use of chemical weapons by the Assad regime, asserting that:

We cannot have a situation where chemical or biological weapons are falling into the hands of the wrong people. We have been very clear to the Assad regime, but also to other players on the ground, that a red line for us is we start seeing a whole bunch of chemical weapons moving around or being utilised. That would change my calculus. That would change my equation.[5]

Despite this assertion, a major chemical weapons attack against a rebel stronghold near Damascus in August 2013 failed to change President Obama’s equation. As his remarks made clear, Obama seems to have been more concerned about the potential of having these weapons fall into the ‘wrong’ hands, meaning the Jihadi elements which have begun leaving their mark on the scene by that time, rather than having them deployed against rebel forces by the Assad regime. More importantly, Obama’s real calculus remained centred on avoiding entanglement in a conflict that by 2013 had clearly devolved into a proxy war pitting many regional players as well as different segments of the population against each other.

What seemed like a brave and wise decision at the time, at least to some observers, created a vacuum on the ground that was soon filled by the Islamic State, a terrorist group launched in Iraq, that President Obama had once dismissed by comparing it to a junior varsity basketball team.[6] By 2016, American jets were finally flying over the Syrian skies, but rather than bombing locations manned by Assad loyalists and militias, the real cause of Syria’s suffering, they were targeting communities that have been invaded by the Islamic State. Their liberation would take years and would exert a tremendous toll on the civilian population. At the same time, Russian jets were busy pounding rebel positions in Aleppo in an intervention facilitated by Iran. Consequently, the survival of the Assad regime over the long haul would soon be assured. The rebels, who at one point controlled most of the country, will soon be forced to occupy small pockets in the Idlib province along the borders with Turkey.

For its part, the US will find new allies among the Kurdish population in the northeast and its operations against the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria will drag on until early 2019. A small number of US troops are still operating in the region to fight against remaining pockets of IS terrorists, The US often finds itself having to mediate continually between Kurdish militias and Arab tribal fighters, while trying to alleviate Turkish fears regarding Kurdish separatist tendencies.

Just when everybody thought that the recent drive by Arab states to normalise relations with Assad has put an exclamation point on his ‘victory’, major protests erupted in the southern parts of the country; in areas deemed to be under regime control; with the protesters demanding nothing less than the ouster of their ‘Dear Leader’, and adopting the same slogan that reverberated through the country back in 2011: ‘the people want to topple the regime’.

A lot has changed and nothing has changed. The leaders of the United States and other democratic powers that have called for the departure of Assad and for a democratic transition in Syria are now facing the same dilemma: where do their values and interests intersect in Syria? Which is costlier in terms of human lives, credibility, and strategic interests: intervention or non-intervention? Or, as things almost always play out eventually: a carefully considered and planned intervention, or a reactive haphazard one?

The Myth of Containment

Nothing shatters the myth of the containability of civil conflicts in our hyper-connected world like the Syrian Conflict does, at least if people are willing to see. With Germany now housing close to a million Syrian refugees, and far right political parties making major headway in provinces and countries all over Europe, not to mention increasing racial tensions in all countries bordering Syria between natives and refugees. With regional powers using the conflict as an opportunity to advance their parochial interests and settle scores with Jihadi elements. With terrorist cells filling the void left by ill-equipped and abandoned moderate rebels, even after the collapse of the Islamic State Caliphate. With the Assad regime transforming the country into the world’s newest narco-state and flooding Syria’s neighbours with the drugs Captagon and Ecstasy. With the possibility that the Russian President Vladmir Putin’s decision to invade Ukraine in 2014 was heavily influenced by the decision of his American counterpart to back down from enforcing his red line on the use of chemical weapons in 2013.[7] While his decision to invade Ukraine again in 2022 seems linked to his perceived successes in Syria since the Russian intervention there began in 2015. With all these developments taking place around us as consequences of the Syrian Civil War, the concept of ‘containable conflicts’ should finally be put to rest. Our modern world has become too connected, hyper-connected in fact, to allow for intractable civil conflicts to be contained and not have far reaching ramifications far beyond their borders.

Though the Assad regime seems to have adopted a wait-and-see attitude vis-à-vis the protests in the Suwaida Governorate in the southern parts of the country. While it keeps focusing its attention on the more violent front in the Idlib Governorate in the northwest, this policy could change at any given moment. For this reason, the United States and its regional allies, especially Jordan and Saudi Arabia, need to consider the importance of early decisive intervention to help secure these strategic areas. A conflict in the Syrian south, which will likely involve Russian airstrikes on critical infrastructure there, ie schools and hospitals, and which will surely rely on pro-Iranian militias in the field, would prove extremely violent, and could lead to a new wave of refugees that will surely destabilise the already fragile situation in Lebanon and Jordan. Terrorist cells, some affiliated with Islamic State, could easily take advantage of any chaos as well. The renewed conflict might indeed physically spread to Jordan and Lebanon. Captagon production will boom, and trafficking will reach far beyond the region’s borders. Nothing will be contained.

The Polarisation Effect

The Syrian conflict has unfolded at a time when the United States and other Western democracies are going through a deeply polarising internal ideological struggle over many vital aspects of their contemporary existence, including: the nature of their collective identity and its legitimate historical sources; how diverse their societies could or should be; their place in the world, past, present, and future; and what political current is genuine, patriotic, or progressive enough to lead the way forward. All aspects of foreign policy were being assessed in view of their potential impact on this existential ‘debate’ and its possible outcomes, especially which party will emerge as a winner and which a loser.

In regard to the policy on the Syrian conflict, an unlikely ‘alliance’ of Realists, Progressives, the far right, and the far left carried the day. The alliance was not official of course, and there was no direct coordination between these camps necessarily, but their views on the Syrian conflict converged and heavily influenced both the public opinion and official policies in their countries. For their own particular ideological reasons, each of these camps is unhappy with the existing global liberal order, and they all want to see a much smaller global footprint for the United States and the West, including in such vital international institutions as NATO and the World Trade Organization. How the rest of the world fares as a result of this shrinkage or downsizing is not a major concern of theirs. All of them seem to think that the US and its Western allies are quite capable of shielding themselves from any negative consequences. By advocating a policy of non-intervention in Syria since the beginning of the conflict, then modifying their position to accept a narrow intervention focused exclusively on the Islamic State, their collective hope was for such an approach to weaken the much-reviled Global Order which America and its Western and democratic allies constantly needed to serve and protect.

This is why today, the same camps are busy advocating a similar approach for dealing with the Russian invasion of Ukraine, that is, a policy of non-intervention. Luckily for the Ukrainians, they have to deal with a much wiser and far more pragmatic president in the White House. For while President Joe Biden may not have disagreed with President Obama’s approach on Syria, the double blow to America’s international credibility as a result of failing to enforce its red line there, followed by the dangerously erratic foreign policy of President Donald Trump, and President Putin’s increasingly aggressive tactics, seem to have alerted him to the need for taking a strong stand on Ukraine and against Putin, to save and strengthen NATO—an institution that retains its credibility and necessity in President Biden’s calculus.

Additionally, the liberal interventionists who had been the biggest policy losers in the fight for Syria seem to have learned from their loss and have managed to articulate their position much more clearly, forcefully, and earlier in the conflict. In this, they were helped by Ukraine’s close geographic and cultural ties to Europe and the West. But in Syria, the United States and its Western and democratic allies did not simply betray their values, they also undermined their own interests. Their failure in Syria was not simply a reflection or a byproduct of their own internal crises, it exacerbated them, something that is yet to be acknowledged widely in their decision-making circles. The political elite in the West, it seems, have become too disconnected from the realities elsewhere in the world to fully understand them or appreciate how deeply connected our world has become. Even the liberal interventionists suffer from this handicap. Their willingness to acknowledge the need for intervention does not necessarily lead to proposing the right policies for it or knowing how to manage it. At least they are willing to listen. They are aware of the problem.

Interventionism is not always an expression of some lingering imperialist instinct or a reflection of imperial overreach. In our hyper-connected world, a measure of interventionism by democratic powers is needed as a way of ensuring adherence to certain standards of justice and accountability without which the current transition to multipolarity will be a much more bloody and violent affair than it should be. At a time when there are so many aspiring regional powers rising and flexing their muscles, if a real red line cannot be drawn on mass atrocities, even when they are being perpetrated by relatively weak regimes, such as Assad’s, then this will serve as a green light for more and more. The west will not be shielded from the impact.

Here Come the Worms

The Realists and Co. were not the only ones to have their little moment under the sun at the expense of the Syrian people. There was also Vladimir Putin and his merry band of cutthroats, liars, and thieves: the Wagner Group. There was Iran, and its own Shia militias spread out across the region fighting a 1400-year-old battle against illusory windmills. There were the Islamic terrorist groups who have performed over the years an intricate dance of merger and betrayal reflecting personal disagreements between the leaders and continually changing priorities of their regional donors. Both Russia and Iran benefited immensely from the struggle in Syria, or to be more specific, from the US-led approach to it. Every half measure President Obama adopted was exploited to the fullest by the loitering duo, not simply to strengthen their position in Syria, which has turned into a dual mandate of sorts, but also to improve their regional and global standing vis-à-vis the United States.

This is especially true in the case of Russia where Vladimir Putin, using the various media institutions under his control, flooded the information scene with disinformation and lies about everything related to the Syrian conflict, from the chemical weapons attacks carried out by his aspiring mini-me, Assad, to the humanitarian organisation, the White Helmets, that has been doing an amazing job saving Syrian lives. Amplified by willing ideologues from the progressive, far left, and far right camps. His propaganda proved effective at creating fertile grounds for all sorts of conspiracy theories to take hold.

The anti-war activists in the UK were particularly duped, reacting mostly to what had taken place in Iraq in 2003—the US-led invasion justified in part on the basis of faulty intelligence—rather than what was taking place in Syria since early 2011. They refused to believe any reports on the situation there, even those coming from myriad independent journalists and human rights organisations. Their minds were already made up and they only listened to sources that confirmed their beliefs. In 2013, the anti-war movement was so effective that it put enough pressure on the British Parliament to vote against UK’s participation in any military operations meant to punish Assad following the chemical weapons attack in Damascus. This development, in turn, helped influence President Obama’s decision to back down from enforcing his red line, and to eventually accept a Russian-sponsored deal that saved Assad’s skin. For spite, Yet Assad will use chemical weapons on a number of occasions in the future, as per UN reports.[8]

As for Iran, despite Russia’s presence on the ground and regular airstrikes against its positions by Israel, it has now become so enmeshed within the military and security apparatuses of the Assad regime, to the point of raising alarm bells even within the ranks of Assad loyalists, being cited as one of the major motivations for the anti-regime protests taking place today in Suwaida. Shaikh Hikmat al-Hajiri, one of the top religious leaders of that majority-Druze region, has even called for Jihad against the Iranian invasion of the country, as well as for establishing secular democratic rule. Yet it seems that without a major shakedown of the entire system, ie toppling the regime, Iran’s influence in Syria is here to stay.

Jihadists and terrorists now control a swath of land in the Idlib province along the borders with Turkey. The most powerful group among them is al-Qaeda offshoot that goes by the name of Tahrir al-Sham, and whose leader was released from prison by the Assad regime in early 2011 among hundreds of Jihadis and terrorists in a macabre move designed to give credence to Assad’s claim that he is fighting terrorists. Meanwhile, the Islamic State itself still retains pockets and cells scattered in the Badiyah area, in the Syrian desert stretching from northeastern parts of the country all the way to the borders with Jordan in the south.

The presence of so many war criminals on the scene is bound to complicate issues of stabilisation, transition, and accountability. It also makes them all the more necessary, otherwise, the lesson that will be learned by dictators throughout the world is that impunity will triumph. Indeed, this, it seems is the governing ethos of current global dynamics, and that’s a deadly reality that does not augur well be it for peace, accountability, or democracy, anywhere.

Accountability

To paraphrase President Obama’s favourite quote by Reverend Martin Luther King Jr: ‘the arc of the moral universe is indeed long, but it doesn’t bend towards justice by itself’. Those who believe in justice need to push hard to bring criminals to account. Today, and as we witness the rekindling of revolutionary fires in Syria, bringing to account the war criminals that have devastated the country is more vital than ever.

The list of the war criminals of Syria is long indeed, but its constituents are rather obvious. They include Assad himself of course, as well as his generals in the military and security apparatuses, especially those who orchestrated the liquidation of tens of thousands political detainees in ‘industrial-scale’ massacres not seen since World War II. They also include Russian generals and Wagner mercenaries, Iranian ‘advisors’ and other sectarian operatives funded by Iran, and certain Jihadi elements and operatives affiliated with the Islamic State and other terrorist movements.

Syrians are not waiting for the international community to make its move and are already trying to get a measure of justice on their own working with well-established legal experts. Several trials against lowkey operatives who were apprehended after they fled to various European cities have already taken place or are underway. A trial in France is also targeting two of Assad’s top security chiefs, Ali Mamlouk and Jamil Hassan, for ‘complicity in crimes against humanity and war crimes in killing two French nationals of Syrian-descent’.[9] The two are being tried—in absentia, of course, but the symbolism is nonetheless significant.

Meanwhile, the governments of the Netherlands and Canada have brought a case against Syria before the International Court of Justice ‘for torture and other cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment and punishment of its own population’. The basis for the case is evidence ‘gathered by various bodies, including the International, Impartial and Independent Mechanism, the UN’s investigative body for Syria’.[10]

Despite the significance of these steps, it could be far more effective to establish a special tribunal under the auspices of the United Nations General Assembly, to try Assad himself and all other criminals, and to issue indictments. If the International Criminal Court could issue an arrest warrant against Putin, the head of a nuclear state, there is no reason why an international tribunal cannot issue similar warrants against Assad and other war criminals in Syria. Admittedly, executing these warrants may not be easy, but it’s not impossible either.

Decision-making in democratic states is never an easy process, especially in times of crises, especially in regard to foreign policy, and especially when so many of these countries have a long history of imperialist (mis)adventures. Where the debate about it is never-ending and remains very bitter and highly charged.

Syrians and other peoples from the Global South who look to democracies for help on any issue have to understand that. An American president, for instance, operates under many constraints, and has at any given moment, a number of crises that require his attention, where he has to consider issues of national interests, of global power balance, and of national and international law (because yes, they do really matter). Then, there is always the question of the President’s own worldview, priorities, and predilections. The same applies for many Western leaders as well. So, while Assad can go to Putin, hat in hand, and beg for his support, and while Putin can make that decision without having to consult anyone, no American President or any other democratically elected leaders can behave in a similar fashion when asked for help, no matter how sympathetic to the cause he happens to be. This ‘calculus’ needs to be understood and even appreciated by Syrians. Democracy is messy and we need to learn how to deal with the mess, especially now as a second revolution seems to be looming.

For their part, people in democratic societies have to come to terms with their increasing responsibilities in a hyper-connected and hyper-interdependent world. The lines between foreign and domestic policies are continually blurring, and that requires us to develop a deeper understanding of ‘foreign’ policy. With so many of our citizens being first-and second-generation immigrants, and with so many refugees living in our midst with the promise of more to come, be it legally or illegally, how do we define ‘foreign’ these days anyway? Whether we live within a unipolar or a multipolar world order, order needs to be maintained, that is, policed. There needs to be standards and accountability. A world rife with impunity is poisonous to all, even the most rich and powerful states. If we ever needed to draw a real red line, it should be done now and in regard to mass slaughter. The promise of ‘Never Again’ should not continue to seem so hollow and hypocritical. Peace and stability should never be seen as higher virtues than liberty and justice. Our survival as a civilization existing in a moral universe requires them all.

***

Since the submission of this article in early October 2023, much has taken place: Jordan has carried out several airstrikes inside southern Syria targeting infrastructure and persons affiliated with drug-trafficking, with these strikes occasionally leading to civilian casualties.[11] A court in France issued arrest warrants against Bashar al-Assad and his brother Maher for complicity in crimes against humanity and war crimes.[12] And a new deadly conflict has erupted in Gaza which could pave the way for a larger regional confrontation, according to many analysts. The varied and polarizing global response to this conflict once again shatters the myth of the containability of certain ‘local’ developments. But it also highlights a major moral dilemma that democracies are facing today, as many of the same political actors currently rallying in support of Palestinians have previously opposed intervention against the Assad regime and oppose Western support for Ukraine. While the West may not be responsible for the crises in Syria, Gaza, and Ukraine, its interests and its security are clearly impacted, hence the imperative to reach internal consensus on how to effectively deal with these situations.

*Ammar Abdulhamid is a well-known Syrian human rights activist, author, poet, and political analyst living in Washington, DC. He is the president of the Tharwa Foundation; a nonprofit organisation that encourages diversity, development, and democracy in the MENA region. Furthermore, he is a Parliamentarian and Director of Policy Research at The World Liberty Congress; an organisation that looks to support and speak out for pro-democracy movements. His work over the last two decades has looked to endorse the political and social modernisation of his native country of Syria.

[1] ‘Why Has the Syrian War Lasted 12 Years?’ (BBC News, 2 May 2023) <https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-35806229> accessed 18 December 2023.

[2] ‘Remarks by the President on the Middle East and North Africa’ (National Archives and Records Administration, 19 May 2011) <https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/the-press-office/2011/05/19/remarks-president-middle-east-and-north-africa> accessed 18 December 2023.

[3] Michael R Gordon and Elisabeth Bumiller, ‘U.S. Military Is Sent to Jordan to Help with Crisis in Syria’ The New York Times (New York, 10 October 2012) <https://www.nytimes.com/2012/10/10/world/middleeast/us-military-sent-to-jordan-on-syria-crisis.html> accessed 18 December 2023.

[4] Barbara Plett Usher, ‘Obama’s Syria Legacy: Measured Diplomacy, Strategic Explosion’ (BBC News, 13 January 2017) <https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-38297343> accessed 18 December 2023.

[5] ‘Remarks by the President to the White House Press Corps’ (National Archives and Records Administration, 20 August 2012) <https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/the-press-office/2012/08/20/remarks-president-white-house-press-corps> accessed 18 December 2023.

[6] Shreeya Sinha, ‘Obama’s Evolution on ISIS’ The New York Times (New York, 9 June 2015) <https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2015/06/09/world/middleeast/obama-isis-strategy.html> accessed 18 December 2023.

[7] William Christou, ‘For Syrians, Russia’s Road to Ukraine Started in Damascus’ (The New Arab) <https://www.newarab.com/analysis/syrians-russias-road-ukraine-started-damascus> accessed 18 December 2023.

[8] ‘Security Council Deems Syria’s Chemical Weapon’s Declaration Incomplete, Urges Nation to Close Issues, Resolve Gaps, Inconsistencies, Discrepancies’ (UN Press, 6 March 2023) <https://press.un.org/en/2023/sc15220.doc.htm> accessed 18 December 2023.

[9] ‘France issues arrest warrant for Syria’s President Assad – source’ (Reuters, 15 November 2023) <https://www.reuters.com/world/france-issues-arrest-warrants-against-syrias-president-assad-source-2023-11-15/> accessed 18 December 2023.

[10] ‘The Netherlands and Canada to Bring Case against Syria before International Court of Justice’ (Government.nl, 12 June 2023) <https://www.government.nl/latest/news/2023/06/12/the-netherlands-and-canada-to-bring-case-against-syria-before-international-court-of-justice> accessed 18 December 2023.

[11] ‘Suspected Jordanian air strikes in southern Syria kill 10’ (BBC News, 18 January 2024) <https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-middle-east-68017376> accessed 4 February 2024.

[12] Chris Liakos, Claudia Colliva, and Dalal Mawad, ‘France issues arrest warrant for Syrian President Assad’ (CNN, 16 November 2023) <https://edition.cnn.com/2023/11/15/middleeast/france-arrest-warrant-syria-assad-intl/index.html> accessed 4 February 2024.